'TAPPING' INTO GROUNDWATERS' POTENTIAL FOR AGRICULTURE

The previous post introduced the topics of water and food in Africa, illustrating the unevenness in the distribution and availability while emphasising the concerns related to food production. This second post will look at the potential of groundwater resources for irrigation and improving food security.

Climatic variability in Africa:

Within the African continent, water resources are characterised by extreme spatial and temporal variability in rainfall and temperature. Disparities in rainfall are very high with ‘95% of annual rainfall totals deviat[ing] between 20 and 40% from the mean’ (Carter and Parker 2009). These variations have resulted in water-rich areas in some regions of the continent such as the equatorial zones, while in other regions decline in rainfall has exacerbated drought conditions and increased water stress. With a shifting climate towards warmer temperatures and more variable and unpredictable rainfall, countries, particularly those that rely on rain-fed agriculture (e.g., within Sub-Saharan Africa) face critical threats to their crop and livestock production.

As the largest store of freshwater, there's been growing calls to draw from groundwater reserves to restore economic growth and improve food security within Africa (MacDonald et al. 2021).

Groundwater in Africa

Groundwater forms a key component of the natural water cycle and is found in most places beneath the Earth’s surface. It is derived from rainfall which infiltrates through the cracks, pores, and fractures into the ground. Though more than 75% of the African population uses it as the primary source of drinking water, it remains underexplored for irrigation. Estimates suggest only a percent of the cultivated land area in Africa is irrigated using groundwater, most of which takes place in Northern Africa. However, MacDonald et al. 2012’s first quantitative maps of GWR revealed that Africa's total volume of groundwater storage is estimated to be 0.66 million km3. To put this into context this is more than 100x the annual renewable freshwater resources and 20x the water stored in African lakes.

Yet, prominent metrics of water stress and water scarcity have ignored this vital resource in estimations, by largely focusing on renewable freshwater resources defined by mean annual river discharge (Taylor et al. 2009). The result of this has been a misrepresentation of freshwater availability, in places that have substantial groundwater storage such as sub-Saharan Africa (Taylor et al. 2009). With increasing food demand and less reliable rainfall, using groundwater for irrigation seems promising as groundwater responds slower to meteorological changes than surface water providing a significant buffer against climate variability (MacDonald, Taylor, and Bonsor 2012).

Distribution of groundwater:

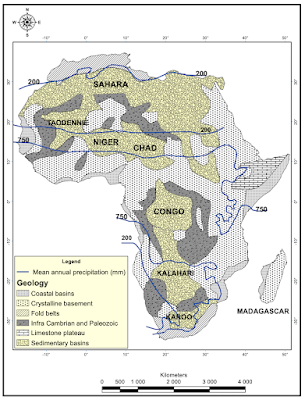

Groundwater represents a fundamental freshwater resource for Africa, but it is not distributed evenly. The largest groundwater storages are found along sedimentary aquifers in Northern Africa (Gaye and Tindimugaya 2019). While the lowest groundwater storages are found in surfaces covered by weathered crystalline basement rock. But, the availability of groundwater cannot be merely deduced from storage, rather it is also dependent on other factors such as the yield of boreholes, depth to groundwater, and groundwater recharge rates (MacDonald, Taylor, and Bonsor 2012). To take an example, the Saharan aquifers have large untapped groundwater reserves but are not actively recharged, thus may be considered non-renewable (MacDonald et al. 2012).

|

| Figure 1: Groundwater regions in Africa based on geology (Source) |

Groundwater management challenges:

As a low-cost alternative, groundwater has been intensively used for domestic water supplies in urban Africa. However, in these rapidly urbanising regions, shallow groundwater is increasingly vulnerable to contamination due to poor waste management and inadequate source protection (Lapworth et al. 2017). Moreover, unconstrained groundwater use for agriculture during the dry season threatens its sustainability. High demand often coincides with low recharge rates causing a decline in water tables and consequently resulting in ground salinisation and increased pumping costs for abstraction (MacDonald, Taylor, and Bonsor 2012). Limited knowledge and inadequate technical capacity at national levels present further challenges to the sustainable provision and management of groundwater in Africa (Gaye and Tindimugaya 2019).

|

| Figure 2: Water being fetched from an unprotected hand-dug well in Nigeria (Source) |

Your posts demonstrates sound grasp of water and food issues in Africa, and the two posts build on each other showing engagement with relevant literarues but the referencing format needs to be improved.

ReplyDelete